I wish everyone had the chance to meet Laurie Steed, or at least to get an email from him. I’ve been lucky enough to know him for several years and been the beneficiary of his gentle, insightful and uplifting guidance in my own writing practice.

I wish everyone had the chance to meet Laurie Steed, or at least to get an email from him. I’ve been lucky enough to know him for several years and been the beneficiary of his gentle, insightful and uplifting guidance in my own writing practice.

Laurie is a true writing soul – a person who believes, utterly, in the importance of words, and their capacity to carry beauty and significance, in even the most minor interactions. But not only is he a mentor-extraordinaire, he’s also an extremely talented writer in his own right, and he good news is, he has a book out, so now everyone does have the chance to experience his wonderful words.

You Belong Here is the story of the Slaters. We begin with Jen and Steve, who meet, marry and find themselves living in Perth with three young children almost before they can blink. The Slaters have their challenges – divorce, mental illness, sibling rivalry – all of which threaten the family’s very foundations. But there is still love.

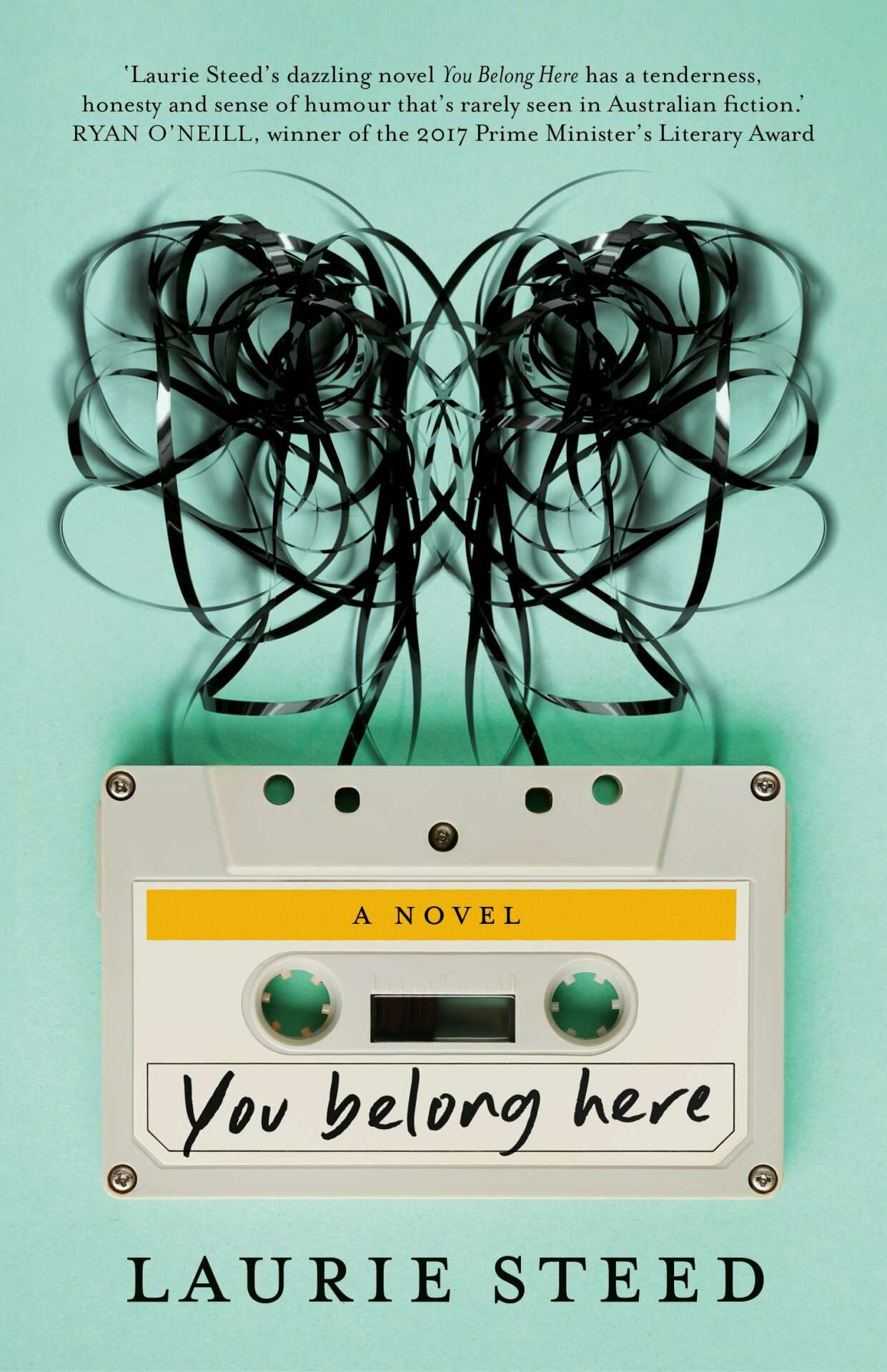

Apart from having one of the most clever and beautiful covers I’ve seen, You Belong Here captures a certain truth about families that will make you reflect on your own. The Slaters aren’t just one family, they’re every family and it’s a pleasure to welcome Laurie to the blog to answer some questions about the book and his process for writing it.

What was your original vision for this book? Does the end product bear resemblance to that vision?

In a word, yes. Which is not to say that the book has not undergone radical changes in the drafting and redrafting process, more I made these changes in line with the original idea of the type of book I wanted to write, and the ethos behind the book.

In a word, yes. Which is not to say that the book has not undergone radical changes in the drafting and redrafting process, more I made these changes in line with the original idea of the type of book I wanted to write, and the ethos behind the book.

The original and final concept was to write a family love story, with all family members represented in that love story. At around two-thirds of the journey in, a publisher suggested rewriting my book as a single-protagonist novel with publication as the likely result. I chose not to do this because that wasn’t the book I wanted to write. It was a smart, sensible way to simplify my story. While I’m smart, I’ve never been all that sensible…and indeed, I started writing short stories for the opposite reason. I wanted to be free, to play, to experiment with form, and take risks.

My vision for You Belong Here was to be as original as possible, to be different. In this respect, the end product holds up to that vision, that willingness to experiment with story types and to portray love upon the page in a world that’s often fuelled by irony and knowingness.

You Belong Here was never meant to be a book about knowing; it’s a book about feeling and understanding

I understand the book was initially conceived as linked short stories, which is interesting. Was that an artistic choice, or a way of shielding yourself from the intimidatory nature of ‘the novel’?

You Belong Here is my fourth full-length novel manuscript, and I’ve written around 200 short stories too. While I’d always thought I needed to write a novel to break through, I’d also been writing short stories. The numbers didn’t lie: around fifty percent of my fully-developed short stories had been picked up for publication, whereas none of those first three novel manuscripts were what I’d wanted them to be.

I’m not sure I conceived YBH as linked short stories. Short stories were more how I began the family journey, a way to get to know each of the characters, to commence the process of integration. There are other ways to write a family novel, no doubt, but for me, it was about equality of voice, a non-judgmental space in which to view, rather than overtly create the characters.

You say life is a series of moments, and that’s always how I’ve viewed my life, and by extension, the world at large. This could be something as simple as my friend Alastair tapping someone on the shoulder and saying, ‘Camille Palinski,’ to a guy who, it turns out, was not Camille Palinski, or it could be more the ‘stuff’ of life; yourself, two, three wines in, propped up against a bedroom wall while your best friend cries in her bed; trying to be there for her, best you can, but wishing you could do more to slow the tears.

In time, I realised short stories were my controlled variable: a form in which I was familiar, a safe space to experiment. They worked to a point but would stop me from fully connecting this particular narrative. As a collection, You Belong Here was a schematic. The moment I chose to make it into a novel it became a living, breathing thing, the breadboard covered in crumbs, the TV left on, call and answer from room to room, voices echoing up and down the hallways.

The concept of ‘family’ is such an interesting, rich subject for exploration in literature. After all, we are all born into a family. We all have a longing for connection and family members seem the obvious people with whom to connect. However, as the Slaters demonstrate, we seem to manage to stuff it up pretty royally. Why is that?

I can only speak for the Slaters and my own experience in life. I do know of certain familial anomalies. One strand of my extended family, The Waltons, for example, had a situation where one sibling gave another sibling one of their kidneys, and it wasn’t a big deal for them. They just did it, because that’s what families do.

Most families fall somewhere between the Waltons and the worst, sometimes close, sometimes distant, wanting to connect but often falling short. Why do we stuff it up so royally? Because we’re human beings, and because the longer you spend on the earth, the more likely you’ll play both hero and villain, victim and perpetrator. Why does it hurt to be in a family? ‘Because these people weren’t brought into this world to be what you want them to be, but rather what they need to be.

In my own family, there’s a good day for every bad day, a moment of wisdom for every time they do my head in. I’m sure I do their head in too. Maybe it’s not so much about connection as it is about growth, where possible. And in time, it’s about a decision, or many decisions as an individual, evaluating what’s been given, what’s worth keeping, and what no longer serves your thoughts and feelings.

Another strength of this book is the dialogue. It has the absolute whiff of authenticity, mainly because the characters never quite say what they want to, and there are many gaps – which has the lovely effect of giving the reader the space to fill them. Any tips here for how to achieve that effect?

Thanks for the kind words! I’ve always prioritised dialogue in my work; I think because it’s an extension of voice, both regarding character and the author’s framing of reality. There’s also no better relationship code than the words we say to another, the way in which we say them.

How to write good dialogue? I teach about three uses of dialogue in a narrative, namely:

- To develop character

- To accelerate the plot

- To increase tension

And yet, spelling it out like that ignores the listening to dialogue, the clocking of cadence in people’s conversations, the way somebody talks on one end of a phone call.

As with all things, it’s about paying attention to how people interact, the words they include or exclude to generate meaning. With all things communicated, there’s almost always some form of subtext, so that, if nothing else is the gateway to good dialogue, working out what someone’s really saying, beneath the words that are being spoken.

What’s your relationship with your characters? Is there ever a danger for an author to get too close to them?

My God, do I love them. How could you not, when you’ve spent so much time around them, felt their fears and insecurities? When you know their story, or as much of it as they’re willing to give, have seen them rise and fall, been subject to things not fair or kind but more a by-product of life, an unhelpful remainder of loving and living on this earth?

For my style of writing, I’m not sure there’s such a thing as getting too close. The point is to love these characters, or at the very least empathise with what they have to work with, and that includes Jen and Steven as well as the kids. To that extent, I regularly talked to my characters in and outside of the book. I took them places, wrote them letters, made them playlists, cried with them until they felt as real to me as my own family.

Regarding structural intimacy, that’s slightly different. You Belong Here (the published book) originated from a manuscript that’s double the size, encompassing 52 chapters and four generations of the Slaters. A lot of what fuels the characters, then, is not in the finished book but beneath the surface, imbued with the fabric of the narrative. It’s essential, as an author, to give the reader only that which truly matters about the character, as opposed to their entire life story.

In some ways you’re their master, in some ways a counsellor, listening for clues, teasing out the greater story, and in many ways you’re their best friend: listening when no one else does, and leaving a light on when all else is darkness, and they’re struggling just to show up on the page.

Do I see myself in one character more than the others? Not really. If anything, I’m more a part of the story itself, sometimes surfacing in a side character or part of a main character’s narrative arc or interests. I listened to Faith No More, watched movies in Innaloo, and made late night visits to Hungry Spot. I worked at the Dome in Mount Lawley where Emily and Jen shared a cappuccino and mulched the airport where Steven worked in the 1980s.

You are renowned for your mentoring prowess with emerging writers, and I think one of your many strengths is your ability to ask the right question. Is this how you see the role?

The hardest part for most writers, I feel, is the lack of consultation. I know that when I was emerging, there were few mentors I could really connect with, and those I reached out to had their own fears and insecurities and hurt more than they helped. Which is not to say that I didn’t learn from them (resilience is a helpful skill to have cultivated, whatever the source origin,) more I’d not felt supported, or guided under their tutelage.

There are certain truisms about writing, and the most empowering is to know that as the writer, you will ultimately do the work. I attended a workshop in 2007 with Rebecca Sparrow where she gave us an editor’s name, a way to get our work out there. She said, ‘You might wonder why I’d give this out to the entire group, but only one or two of you will get in touch with her.’

I decided on the back of her guidance to be that writer, the one who took the opportunity and ran with it. And while Rebecca gave me the contact, I still had to pitch my piece and start the journey.

Mentors do this all the time; they set up the mise-en-scene, and see if the author goes with it. Good mentors are rare, of course. But so are writers who are willing to work hard at their craft, never settling for OK when amazing is possible.

My advice, then, is simple: to always stretch one’s self as a writer. To be original when others are imitating; to be brave when others are cautious; to strip back what’s taught and work towards an intuitive understanding of what makes stories tick, and why they’re worth telling in the first place.

What’s next for Laurie Steed? Can you tell me what you’re working on now?

I’m happy to talk more about what’s in the works, although I’ve not yet focused on one particular project. I have a partially completed short fiction collection called The Doppler Effect about emotional intensity, as rendered through media formats (video games, podcasts, etc.) and I’m also still working on The Bear, about two amateur filmmakers in their mid-twenties searching the world for the perfect film location. I’m also keen to write a fictional portrayal of R ‘n’ B and hip-hop culture in Perth in the late eighties and early nineties. I’m particularly interested in how Asian, African, and Anglo Saxon teens embraced American music to explore their isolated satellite city of video arcades, half-court basketball tournaments, and forever-skipping Discmans. It’s potentially contentious territory, though, given the cultural and gender-based responsibilities inherent in the project. Any drafting would need to be done in consultation with any number of racial groups and with a wholly inclusive attitude to ensure I’m working with fully-formed characters, and well-researched intent to ensure an accurate, inclusive portrait of the city as it what as the time.

As to which takes priority, I’m less sure. At the moment I’m enjoying being back in the real world, and away from the Slaters. God love them, of course, but eight years is a long time to be with the same family!

Why writing?

Put simply, writing makes sense to me. While I’m surprised I ended up in fiction writing (I also have degrees in film and video, journalism, and editing and publishing,) I’ve always been interested in communication, and the ways in which we make sense of the world.

On the page, I’m measured, composed. My feelings and the feelings of my characters make sense to me. In life, that’s not so true, and often I struggle to understand the rules or conventions of a situation. I’ll sometimes call people out on this, say, ‘Please, tell me how this works,’ or ‘How are you feeling, really?’ and they’ll baulk, it’s not in their interests to be that real. I guess people have a lot invested in their reality.

Writing, then, allows me to walk better, and with more care into the world. Anything I don’t understand in life is opened up on the page. The things I love or fear in life read infinitely better on the page. It’s as though the light is brighter; I spot a scar, or blemish I might otherwise miss.

I learn to accept, to feel and to forgive. It’s like a lifetime course in being whole, day by day, from story to story.

Laurie Steed is the Patricia Hackett Prize-winning author of You Belong Here, published by Margaret River Press. His fiction has been broadcast on BBC Radio 4 and has appeared in Best Australian Stories, Award Winning Australian Writing, The Age, Meanjin, Westerly, Island, and elsewhere. He is the recipient of fellowships from The University of Iowa, The Baltic Writing Residency, The Elizabeth Kostova Foundation, The Katharine Susannah Prichard Foundation and The Fellowship of Writers (Western Australia). He teaches Creative Writing for Writers Victoria, is the editor of Shibboleth and other stories, and has previously worked as an advisory consultant for the Australia Council for the Arts, the Small Press Network, and The Emerging Writers Festival. He lives in Perth, Western Australia with his wife and two young sons.